Coifs are regarded, certainly among English Civil War re-enactors, as the thing that women must wear on their heads. It is a little more complex than that, and looking at women’s probates across the Stuart period you can see a distinct dividing line; pre 1650 90% of the non-hat headgear for women are coifs, post 1650 90% of the non-hat headgear are hoods. Unsurprisingly Gregory King’s 1688 “Annual consumption of apparel” does not list coifs at all, but has two sections for women’s non-hat headwear, “Hoods, dressing and commodes” of which he believed there were 400,000 a year, and the less common, but more fashionable, “Tours and locks” of which there were only 4,000 a year. (1)

Non Coifs

| Figure 1 William Dobson's portrait of his wife wearing a hood. 1635-40. Tate Gallery |

While pre 1650 coifs were by far the most common women’s headgear, there are references to other types of headgear. In the early years of the century French hoods were still around, in 1604 Elizabeth Jenyson left her daughter, “both my french hoods, [and] my bonegrace.” (2) Fynes Moryson in 1617 described a bongrace as “A French shadow of velvet to defend them from the sunne …now altogether out of use with us.” (3) Despite Moryson’s comment, bongraces do continue in the records, though they are uncommon as well as unfashionable. Their use and make up changes in two ways. Firstly, they become used for children, “Burn-graces in Summer to save childrens Faces” (4). In 1650 one of Edward Harpur’s daughters, Esther, is given “a head lace and a bowne grace” (5 p. 271) Secondly, although the OED says it is difficult to distinguish, they may have become more of a hat, though certainly still something shading the face, as in a 1690 description, “her Bongrace was of wended Straw.” As Moryson mentioned, another term used for the bongrace was shadow. Florio writes of “bone-graces, shadowes, vailes or launes that women use to weare on their foreheads for the sunne.” (6) Lawn was a fabric that was used for shadows, Henry Best wrote that, “Lawne..is much used for fine necke-kerchers, and fine shadowes.” (7) In 1637 George Weston had among other goods in the hold of his ship “two newe shadows for women.” (8 p. 104)

By the 1630s hoods were making

their appearance as an item of soft headwear among the gentry and nobility. In

1633 the Howard of Naworth accounts show “for one black taffatie hudd for Mrs

Elizabeth Howard 3s” (9) In 1641 the Seymour

accounts show several hoods being purchased for “the young ladies” including “for

two white scarcenett hoods for my Lady Jean 7s” and “two black taffetie hoods

for my Ladie Francis, 7s” (10) The accounts for the

household of the Countess of Bath, which cover 1639-1654, have no purchases of

coifs, but a large number of hoods. (11) The type of hood that may have been purchased is shown in Figure 1, a portrait by William Dobson of his wife Judith.

Prices, Purchasing and Making of Coifs

Coifs appear at all levels of society and a vast range of prices, from as little as one penny each for three linen coifs in 1610 (12), to fifteen shillings for “a gould quoife” belonging to Venetia Stanley in 1624 (13), although most of the value of that would have been in the gold work. An example of a gold and silver work coif survives in the Burrell collection in Glasgow, and is shown in Figure 2, the link to the museum record has images of the reverse.

| Figure 2. Gold and silver worked unmade coif in the Burrell Collection, c.1610-20. CC BY NC 4.0 |

Coifs could be purchased ready-made. In 1610 Philip Helwys, a merchant of Ipswich, had 93 coarse coifs in stock, valued at 2d each. (14) In 1624 the peddler and widow Avis Clarke, had “nine quives of black and tawney 3s” and “aleven drawne work quives 3s,” they were therefore worth between 3d and 4d each. (15) In 1634 Thomas Nelmes, a Bristol grocer, had both blew and drawn work coifs in stock ,the blew were 2d each and the drawn work 3d. (8)

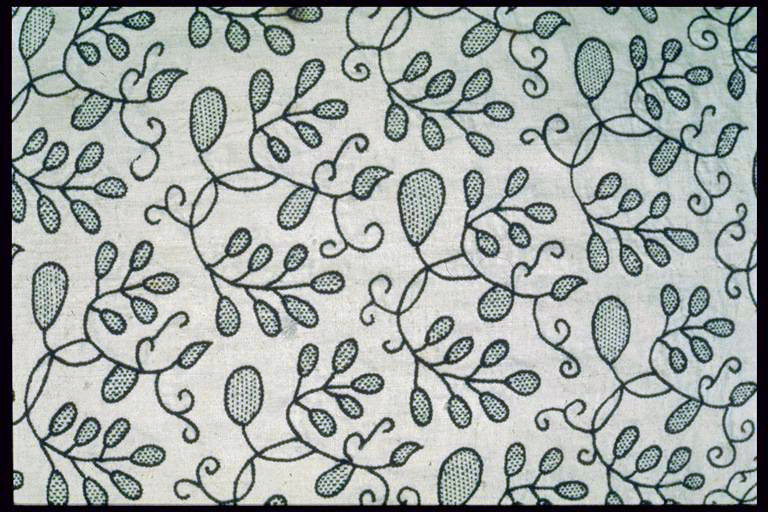

Coifs could also be made at home, though records for this are few. In the Harpur probate accounts are several records of purchases of cloth for making coifs for the Harpur daughters. In 1650 purchase was made of “2 yards of calico for Anna and Sarah with 1 yard of holland for coiffes 5s 6d” and in 1653 “for ½ an ell of holland pro Anna and Saras coifes 3s 6d” (5) The fabric could also be drawn, that is have a pattern drawn on them, for a child or adult to embroider. In the probate accounts of John Tayler of Kent, who had a charge value on his estate of just over £16, so he is not rich, there is for “draweing of a coyfe for the said minor and for Cruell.” (16 p. 93) His accounts end in 1630, and it would seem from this that his daughter embroidered her coif in crewel wool. Crewel wool coifs do not survive, but a jacket of roughly the same date, embroidered in a fine black wool, is in the Museum of London collection. Figure 3 shows a detail of the design of barberries on the jacket.

|

| Figure 3. Barberries embroidered in fine black wool on linen from a jacket in the Museum of London. 1610-20. |

Who wore coifs and what were they made from?

At the lowest levels of society poor children were provided with coifs by overseers of the poor and other charitable institutions in both the Suffolk and Kent records. (16 pp. 51-54). In Christ’s Hospital, Suffolk, older girls were provided with coifs made from lockram, while the younger girls had coifs of check lined with hamborough. (16 p. 51) Both lockram and hamborough are linens, which seem to have sold for between 7d and 12d an ell. (17 pp. 163, 172, 191)

Far more expensive and of better quality was holland, another type of linen, and Spufford’s analysis of the prices of holland between 1610 and 1660 showed an average price of two shillings, at least twice the price of cheaper linens. (18) In 1620 Jane Aubrey, a gentlewoman, left in her will, “a plain Holland coif edged with bone lace.” (19)

Though linen based fabrics are by far the most common, coifs could be made from other fabrics. In 1625 Joan Gooch, a widow, left her daughter two fustian coifs. (20 p. 129) It is possible that people had what they might call workaday coifs and holiday coifs, the holiday coifs being of a better quality cloth, the fourteen year old Elizabeth Harnett had coifs of both holland and bustian. (16 p. 93) In 1635 Alice Edmunds left her sister a silk coif, and 3 holland coifs. (21 p. 335) There is also mention of tiffany being used for coifs, this is an expensive, very fine, transparent fabric, which could be either silk or linen. In 1619 “a tiffany coife worth twelve shillings” was stolen in London. (22)

Embellishment of coifs

As has already been discussed coifs could be embellished with embroidery, and lace. In 1612 the Howard accounts show a payment of 18d for “working a coyfe for my lady”. (9 p. 11) Blackwork was a popular choice in the early years of the century, in 1613 “one blacke wroughte quoife worth eighteen pence” was stolen in London. (23) An example of a late 16th – early 17th century coif embellished with black silk embroidery is shown in figure 4. This coif is in the Cooper-Hewitt Collection

|

| Figure 4

Blackwork coif embroidered with a scrolling design of strawberries, apples,

etc, and incorporating birds, butterflies, snails, etc. Public domain. |

| Figure 5. Detail from a coif in Worthing Museum. |

The drawn work coifs mentioned in the stock of Clark and Nelmes, also appear in probate inventories and wills. In 1620 the Howard accounts have “a drawnen work coyfe for my lady 16d” (9 p. 124) In 1632 Elizabeth Lee in Durham left a drawn work coif. (24 pp. 113-4) Platt Hall in Manchester has several coifs from the second quarter of the 17th century that incorporate drawn thread work, and Figure 5 shows a detail from an example of a cut and drawn thread work coif in the Worthing Museum.

Coifs could also be embellished with lace. This was not necessarily an expensive lace, in 1661 ten pence was paid for “a yard and a halfe of lace for a coife” for one of the Harpur daughters. (5 pp. 266-98) A letter from Elizabeth Isham has samples of lace attached that cost two, six, seven and ten pence a yard. (25 p. f.162) The lace was usually used at the edge of the coif, and a drawn and cutwork coif with an edging of a wider lace is shown in Figure 6, it is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

|

| Figure 6. Cut and drawn thread work coif. C.1625. Victoria and Albert Museum. |

References

1. Harte, N. B. The Economics of Clothing in the Late Seventeenth Century. Textile History. 1991, Vol. 22.

2. Wood, H. W. ed. Wills and inventories from the registry at Durham, part 4, [1603-1649]. Publications of the Surtees Society. 1929, Vol. 142.

3. Moryson, Fynes. An itinerary. London : Printed by John Beale, dwelling in Aldersgate Street, 1617.

4. Gayton, Edmund. Pleasant notes upon Don Quixot . London : Printed by William Hunt, 1654.

5. Phillips, C. B. and Smith, J H. Stockport Probate Records 1620-1650. Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. 1992, Vol. 131.

6. Florio, John. A worlde of wordes, or most copious, and exact dictionarie in Italian and English. London : A Hatfield for E. Blount, 1598.

7. Best, Henry. The Farming and Memorandum Books of Henry Best of Elmswell, 1642. London : British Academy, 1984.

8. George, E. and S. eds. Bristol probate inventories, Part 1: 1542-1650. Bristol Records Society publication. 2002, Vol. 54.

9. Ornsby, G. ed. Selections from the Household Books of the Lord William Howard of Naworth Castle. Publications of the Surtees Society. 1878, Vol. 68.

10. Private Purse Accounts of the Marquis of Hertford, Michaelmas 1641-2. Morgan, F. C. 1945, Antiquaries Journal, Vol. 25, pp. 12-42.

11. Gray, Todd. Devon Household Accounts 1627-59. Part 2 . Exeter : Devon and Cornwall Record Society, new series, vol. 39, 1996.

12. Middlesex Sessions Rolls. Middlesex County Records: Volume 2, 1603-25. Originally published London: Middlesex County Record Society, 1887. [Online] [Cited: 18 January 2022.] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/middx-county-records/vol2/pp58-70.

13. —. Middlesex County Records: Volume 2, 1603-25. Originally published London: Middlesex County Record Society, 1887. [Online] [Cited: 18 January 2022.] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/middx-county-records/vol2/pp176-186.

14. Reed, Michael, ed. The Ipswich probate inventories 1583-1631. Suffolk Records Society. 1981, Vol. 22.

15. Jones, J, ed. Stratford-upon-Avon Inventories,volume 1, 1538-1625. Stratford-upon-Avon : Dugdale Society , 2002.

16. Spufford, Margaret and Mee, Susan. The Clothing of the Common Sort 1570-1700. Oxford : OUP, 2017.

17. Spufford, Margaret. The great reclothing of rural England: petty chapman and their wares in the seventeenth century. London : Hambledon Press, 1984.

18. —. Fabric for seventeenth century children and adolescents' clothes. Textile History. 2003, Vol. 34.

19. Victoria County History: Hampshire. Farleigh Wallop Probate Material, 1601-1620. . [Online] [Cited: 20 January 2022.] https://www.victoriacountyhistory.ac.uk/explore/sites/explore/files/explore_assets/2015/10/20/jane_aubrey_gentlewoman_will_inv_hro_1620a-003.pdf.

20. Allen, M. E. ed. Wills in the Archdeaconry of Suffolk 1625-1626. Woodbridge : Suffolk Records Society, 1995.

21. Evans, Nesta, ed. Wills of the Archdeaconry of Sudbury 1630-1635. Suffolk Records Society. 1987, Vol. 29.

22. Middlesex Sessions Rolls. Middlesex County Records: Volume 2, 1603-25. Originally published London: Middlesex County Record Society, 1887. [Online] [Cited: 22 January 2022.] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/middx-county-records/vol2/pp142-150.

23. —. Middlesex County Records: Volume 2, 1603-25. Originally published London: Middlesex County Record Society, 1887. [Online] [Cited: 21 January 2022.] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/middx-county-records/vol2/pp84-94.

24. Briggs, J. and McGhee, R. Sunderland Wills and Inventories, 1601-1650. Publications of the Surtees Society. 2010, Vol. 214.

25. Levey, Santina. Lace: a history. London : Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete