|

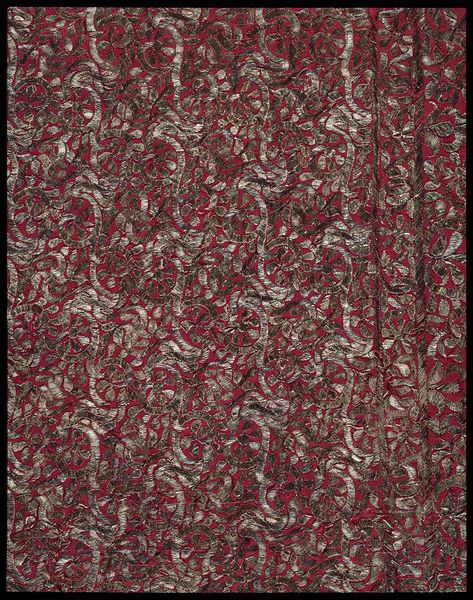

| Figure 1. Detail from V&A |

Origins of the words

Scarf

The term scarf first appears in English, according to the OED, in the middle of the sixteenth century. The first usages are quotes from letters in Foxes Acts and Monuments. The letters are thought to be written by Lady Vane about 1555 and appear in the 1563 edition, “I wyll supplie your request for the scarfe ye wrote of, yt ye may present my handy worke before your captayne.” and in a second letter in the 1570 edition “The Scarffe I desyre as an outward signe to shew to our enemies.” (1) Both these letters may refer to the scarf as a military item, what in the 21st century would probably be called a military sash, or possibly ecclesiastical wear. The use of the word scarf for a fashionable item appears at about the same time. Henry Machyn’s Diary describes Queen Elizabeth on horseback in 1558 wearing “purpull welvwett, with a skarpe about the neke.” (2)

Sash

The word sash, again according to the OED, appears in 1599, but from that point until the third quarter of the seventeenth century relates entirely to eastern wear, and most specifically to turbans, the two words often being conflated. It is not until the 1680s that the London Gazette refers to “Officers Sashes and Ribons.” The use of the term sash in fashionable wear does not seem to appear until the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Shawl

The word shawl is not used for something British women wear until well into the eighteenth century. The word first appears in English in the middle of the seventeenth century, but always referring to what is worn in the East. The first use according to the OED is in a work about the travels of various ambassadors, “The richer sort have..another rich Skarf which they call Schal, made of a very fine stuff, brought by the Indians into Persia.” The first mention of cashmere shawls is in a 1687 work about travels in the Levant, “At all times when they go abroad, they were a Chal which is a kind of toilet of very fine Wool made at Cachmir.”

Fashionable Use of Scarves

By 1587 scarves were one of the many things that Stubbs thought to complain about, “They must [he writes] haue their silk scarffes cast about their faces & fluttering in the winde with great tassels at euery end, either of gold, siluer or silk.” (3) and “some weare scarffes from ten pounds apiece, vnto thirtie pounds or more.” Stubbes does not indicate whether these scarves are worn by men or women.

In men’s probate inventories where colour or fabric is mentioned they are usually black silk, but this does not apply to the aristocracy. The 1617 inventory of the wardrobe of Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset includes, “one needleworke scarffe of flowers of silke silver and gold wrapt in a carnation taffetie” (4). Being royalty doesn’t appear to have stopped people stealing from you, the three people who in 1641 “broke burglariously into the King's dwelling-house called St. James House," stole among other items “three imbrodered scarfes worth six pounds” (5)

| Figure 2 Hollar's Autumn 1644 |

Scarves appear more frequently in women’s probate inventories. Frances Jodrell, spinster, in 1631 owned both “a whyte scarfe with a silver fringe” and “a greene scarfe with gold fringe”. (6) These scarves were often embellished with lace, usually of gold or silver, the General Account book of Rachel, Countess of Bath has the purchase of “a fair laced scarf” (7) The famous beauty Venetia Stanley had two scarves stolen from her in 1624; “a scarfe embrodered with silver worth ten shillings” and “a blacke silke scarfe embroydered with silver worth twenty shillings”. (8) Scarves are sometimes purchased at the same time as a hood, and these could be worn together as can be seen in Hollar’s 1644 engraving entitled Autumn (Figure 2, Hollar Collection), the scarf is round the shoulders and tied in a knot at the front. In 1651 the account books of Rachel, Countess of Bath have “for 3 hoods and a double and a single scarf for my Lady £1 3s” (9)

Scarves often accompanied less formal dress, as Aphra Behn put it, “Your frugal huswifery Miss…in a long scarf and nightgown” (10), and Van Dyck often depicted his female sitters with a carelessly placed diaphanous scarf, as in the image of Beatrice, Countess of Oxford. (Figure 3, Private Collection)

Scarves for mourning

| Figure 3 Van Dyck, Countess of Oxford |

Black scarves were sometime provided for mourning. At the death of Sir Richard Piggott, Sir Ralph Verney wrote, “We that bore up the pall, had rings, scarfs, hatbands, shamee gloves of the best fashion.” When in 1678 the Bristol merchant taylor George Goswell died, £1 19s was spent on hatbands and scarves (11) and in 1692 11s 6d was paid for “hattbands and scarffs” at the funeral of Thomas Blundy an innholder. (12) If the dead person were female the scarves might be white, as Pepys comments, “the rest of the maids had their white scarfs, having been at the burial of a young bookseller.” (13)

Military Use of Scarves

The use of the term scarf for what later is referred to as a military sash, also dates back to the sixteenth century. In Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing Benedick asks, “What fashion will you wear the garland of? About your neck, like an usurer's chain? Or under your arm, like a lieutenant's scarf?” In probate inventories, even with non military men, a scarf is often paired with a sword, as in the 1640 probate of the yeoman William Paice, “a sword and scarf £1.” (14) Similiarly in a will of 1627 Edward Blosse, another yeoman, leaves to his cousin “Robert Kettle [a] training scarf and sword & a pair of fine white jersey stockings.” (15)

A more obvious military purchase is when, at the time of the Bishops’ Wars, the Howards of Naworth Castle in Cumberland, purchase “for stammell, white fustian, taffatie and silver lace for skarffes, and other thinges necessarie for 4 sutes for my Lord's light horsse menne, bought at Penreth and Carlile by bills £8 2s 10d” (16) Likewise when Mr Bold, a member of the Earl of Bath’s Household, goes to join the King’s Lifeguard in 1643, a scarf worth £3 10s is purchased for him. (17)

| Figure 4. Johnson. Sir Alexander Temple |

Men were often had their portraits painted wearing a scarf either diagonally, across the shoulder and down to the hip, as in Cornelius Johnson’s 1620 portrait of Sir Alexander Temple, whose scarf has a diaper pattern in gold (Figure 4, Yale Center for British Art), or around the waist as in Dobson’s c.1645 portrait of an unknown officer wearing a scarf with a gold fringe. (Figure 5: Tate Gallery, CC-BY-NC-ND) The Victoria and Albert Museum have three survivals of seventeenth century military style scarves: (c.1600, (no image), 1625-49 a detail from this example is Figure 1, and 1636-42, this highly embroidered example has connections to Charles I.

During the English Civil War certain colours of scarf were considered to indicate allegiances. In a 1644 publication the comment is made that, “every horseman must wear a scarfe of his Generalls Colours and not leave it off neither in his quarters nor out of his quarters, it being an ornament unto him.” (18) A ruse Clarendon records is that, “They [Royalist troops] had marched, from the time they left Oxford, with orange-tawny scarf's and ribbons; that they might be taken for the parliament soldiers.” (19)

Ecclesiastical Use of Scarves

| Figure 5. Dobson. Unknown Officer |

References

1. The Unabridged Acts and Monuments Online or TAMO (The Digital Humanities Institute, Sheffield, 2011). Available at: http//www.dhi.ac.uk/foxe

2. Machyn, Henry, The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant-Taylor of London, 1550-1563. Originally published by Camden Society, London, 1848. Available at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/camden-record-soc/vol42/pp169-184

3. Stubbes, Phillip, Anatomy of abuses, 1583. Available at: https://archive.org/stream/phillipstubbessa00stubuoft/phillipstubbessa00stubuoft_djvu.txt

4. MacTaggart, Peter and MacTaggart, Ann. The Rich Wearing Apparel of Richard, 3rd Earl of Dorset. Costume. 1980. 14, 41-55, 51

5. Middlesex Sessions Rolls: 1641. In: Middlesex County Records: Volume 3, 1625-67. Originally published London: Middlesex County Record Society, 1888. Available at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/middx-county-records/vol3/pp75-79

6. Phillips, C. B. and Smith, J. H., eds. Stockport probate records, vol 2, 1620-1650. Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1993. vol. 131, 315-22

7. Gray, Todd. Devon Household Accounts 1627-59. Part 2 Devon and Cornwall Record Society, new series, 1996. vol. 39, 264

8. Middlesex Sessions Rolls: 1624. In: Middlesex County Records: Volume 2, 1603-25. Originally published London: Middlesex County Record Society, 1887. Available at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/middx-county-records/vol2/pp176-186

9. Gray, Todd.. Devon Household Accounts 1627-59. Part 2. Devon and Cornwall Record Society, new series, 1996. vol. 39, 160

10. Behn, Aphra,The Town Fop, 1677

11. George, E. and S., eds. Bristol probate inventories, Part 2: 1657-1689. Bristol Records Society publication 2005 vol.57, 92

12. Mortimer, I. ed. Berkshire probate accounts 1583-1712. Berkshire Record Series, 1999. vol. 4, 246

13. Pepys, Samuel, Diary 20th January 1659/60. Available at: https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1660/01/20/

14. Victoria County History: Hampshire: Basingstoke Probate Material 1631-40. Hants. RO 1640A/130. Available at: https://www.victoriacountyhistory.ac.uk/explore/sites/explore/files/explore_assets/2015/01/20/will_inventory_of_william_paice_yeoman_hro_1640a-130.pdf

15. Allen, M. ed. Wills of the Archdeaconry of Suffolk, 1627-1628. Suffolk Records Society, 2015. vol 58, 36

16. Ornsby, G. ed. Selections from the Household Books of the Lord William Howard of Naworth Castle. Publications of the Surtees Society, 1878. vol. 68, 359

17. Gray, Todd. Devon Household Accounts 1627-59. Part 2: Devon and Cornwall Record Society, new series, 1996. vol. 39, 118

18. John Vernon The young horse-man, or, The honest plain-dealing cavalier. London: printed by Andrew Coe, 1644. Available at EEBO, Early English Books Online, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebogroup/

19 Clarendon, Edward Hyde, Earl of, The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England

20. Arnott Hamilton, J. The Stole and the scarf. Journal of the Church Service Society, 1946. https://www.churchservicesociety.org/sites/default/files/journals/1946-27-37.pdf

21. Cunnington, P. and Lucas, C. Costume for Births, Marriages, and Deaths. London: Black, 1972

22. Vaisey, D. G. ed. (1969) Probate inventories of Litchfield and district 1568-1680, Historical Collections for a History of Staffordshire, Fourth Series, vol. 5, 255