The giving of rings “for a remembrance” was common in early modern wills, and many survive. Memento mori rings, reminding the owner that death comes to everyone, had been around since the Middle Ages, and often featured a skull or death’s head. These could sometimes be incredibly ornate, as in the mid 16th century example from the British Museum in Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1: Memento Mori ring. 16th century. British Museum |

The idea of rings to remember a specific person is separate from the memento mori rings, though there is some overlap. The will of Sir Thomas Hesketh (1548-1605) of Lancashire (he is buried in Westminster Abbey) left, “To everye one of my brothers and sisters [12 people] a ringe of golde of the valewe of 40s with a death's head and this inscription “sequere me,”” (1 p. 165) Sequere me means follow me. It might have looked like this example (Figure 2) from around 1600 in the Victoria and Albert Museum. In 1648 Jasper Despotin, a doctor of physick left “ten rings of gold...with a death's head.. to the value of twenty shillings a peece..to be disposed of amongst my friends.” (2 p. 200) Shakespeare in his 1616 will requested that rings for his wife and daughter be inscribed with the words “Love my memory”

Figure 2: Death's head ring. c.1600. Victoria & Albert Museum

Sometimes people might be given the option of a ring or money, the money presumably to have a ring made. These gifts could be very hierarchical. In 1608 Dorothy Scaresbreeke, a single woman, left to her uncles, “to eyther of them a rynge of 20s pryce or so muche in moneye.” Her three sisters, aunt and two female cousins got rings or money equivalent to 13s 4d, and her four brothers in law, her brother, his wife, and a friend all got rings or money to the value of 10 shillings. (3)

Sometimes the rings would be inscribed with the name or initials of the giver, and perhaps their date of death. In 1619, Jane Johnson, widow of an esquire, left in her will “every one of them [8 people] 20s a piece to make them hoope rings with my name therein written for a remembrance.” (4 p. 132) This example in the Museum of London (Figure 3) carries the inscription around the inside of the ring, “Oh my sister, my sister, R.H. Jan 22. 1670” Another ring from 1670, which was discovered by a metal detector in 2008, has on it the inscription 'Prepare to follow FV. Ob: 16 May 70'. This has enabled the Elmbridge Museum, where the ring is now held, to be certain that this ring was made in remembrance of Sir Francis Vincent who, according to the local parish register, “dyed May 16, 1670, between 7 & eight of ye clocke in ye morning, and was buried on Friday night following, being ye 20th day of ye same month.” In his will Sir Francis specified “To my loving sister Mrs Katherine Vane the sum of Ten Pounds wherewith to buy her a Ring. To my said cousin Matthew Carleton three pounds & to his wife forty shillings to buy them rings. To my loving brother and friends Sir Walter Vane, Sir William Harward & Arthur Onslow the sum of Ten pounds a peece to buy them rings.” (5)

Figure 3: Mourning ring. 1670. Museum of London

So far most of the people mentioned have been gentry, but this was not always the case. In 1632 a blacksmith, Edward Filbrigg left to four people “10s each to them each a ring of gold to wear in remembrance of me.” (6 p. 201) In 1634 Richard Copping, a yeoman, left “my loving friend Mr Doctor Rames 40s to buy him a ring to wear for my sake.” (6 p. 287) Those who acted as executors of wills were often left rings, Philip Addams, a currier, wrote in 1637, “I have made Henry Wilson, innholder, Henry Lawrence, butcher and Thomas Cresnar, apothecary, all of Bury, my exors and give them 20s a piece for their pains to buy a gold ring and to wear it for my sake.” (7 p. 135)

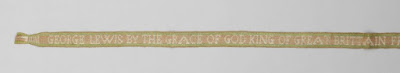

The cheapest ring I have among my records is 5 shillings which Randle Astley, a yeoman, left to Millisaint Bannester in 1641 “to buy a ring with.” (1 p. 62) The most expensive was £10 left by Sir Francis Vincent in 1670, as already mentioned, and Dorothy, Lady Shirley in 1634 “to my loveinge kinsman George Purify esquire.” (8 p. 34) Where a metal is specified it is usually gold however, when looking at rings, not necessarily mourning rings, which have been found and entered into the Portable Antiquities Database, a different perspective appears. A search for finger rings and medieval gives 1142 copper alloy, 861 silver and 675 gold, while a search for post medieval finger rings results in 1296 copper alloy, 1138 gold and 431 silver. These copper alloy rings are not valuable enough to appear in wills, but some of the survivals are certainly mourning rings, as in a sixteenth century example inscribed memento mori. The rings were usually decorated in black enamel as in this gold and enamel example (Figure 4) found at Pennard in Wales and now in the National Museums Wales, it is inscribed inside with the motto “Prepared bee to follow me.”

|

| Figure 4: Pennard mourning ring. National Museums Wales |

The giving of rings continued into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1710 the widow Jane Edmonds left, “unto my sonne in law...and his wife twenty shillings a peice to buy each of them a ring to wear at my funeral” (9 p. 195) The example below is in the Museum of London and bears the inscription “Sam Forth obt 9 Aug 1724 æta 36”, he was a Southwark brewer whose will included bequests for mourning.

|

| Figure 5: Mourning ring for Samuel Forth. Museum of London |

References

1. Earwaker, J.P. Lancashire and Cheshire wills and inventories 1572-1696. Manchester : Chetham Society, 1893.

2. Tymms, S. ed. Wills and inventories from the registers of the Commissary of Bury St Edmunds and the Archdeacon of Sudbury. London : Camden Society, 1850.

3. Presland, M. ed. Angells to Yarnwindles: the wills and inventories of twenty six Elizabethan and Jacobean women living in the area now called St. Helens. St Helens : St. Helens Association for Research into Local History, 1999.

4. Wood, H. W. ed. Wills and inventories from the registry at Durham, part 4, [1603-1649]. Publications of the Surtees Society. 1929, Vol. 142.

5. Elmbridge Museum. Cobham mourning ring (17th century). [Online] [Cited: 4 November 2022.] https://elmbridgemuseum.org.uk/collections/narrative/cobham-mourning-ring-17th-century/.

6. Evans, Nesta, ed. Wills of the Archdeaconry of Sudbury 1630-1635. Suffolk Records Society. 1987, Vol. 29.

7. Evans, Nesta, ed. (1993) Wills of the Archdeaconry of Sudbury, 1636-1638. Suffolk Records Society. 1993, Vol. 35.

8. Nicholas, J. G. ed. The Unton inventories: relating to Wadley and Faringdon, co. Berks. Reading : Berkshire Ashmolean Society, 1841.

9. Bricket Wood Society. All my worldly goods: an insight into family life from will and inventories 1477-1742. 2nd ed. Bricket Wood : Bricket Wood Society, 2004.