“Like as a Silk-Stocking, which when 'tis not gartered, falls upon the Foot.” (1717) Garters have been used for centuries to stop stockings from falling down (think back to the founding of the Order of the Garter in 1344) but what were garters like in the seventeenth century?

Materials and decoration

For the common person garters could be made from almost any type of wool fabric, there are specific references to worsted, so the Frewen accounts in 1631 have “for a payer of worsted garteres 10d” (1). In 1637 a grocer in Kent, James Kennard, has “worsted garters” in his stock. (2) A term often used is list, as in “Garters of Lystes, but now of silke”. (3) List in this context can have two different meanings: some have interpreted it as meaning the selvedge edge from a fabric because statutes for cloth at the time speak of the distance they must be “between the lists”, however it can mean simply a strip of cloth. Petruchio in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew comes, “gartred with a red and blew list”.

Narrow wares, that is braids, ribbons etc., could be used to make garters. In 1644 Rachel, Countess of Bath, spends “for gartering ribbons 7s” (4 p. 250) Gartering could be purchased by the roll, in 1632 the mercer Thomas Harris has in stock, “9 doz. of gartring in the roule at 15d. doz. 11s 3d” and “9 doz. of narrow gartring in the roule at 9d. the doz. 6s 9d” (5 p. 114) In 1623 the tailor Ambrose Pontin has “girdles, laces, gartering and pinnes” in his stock. (6 p. 47) The miniature garters that accompany the two dolls from the 1690s, Lord and Lady Clapham, are narrow wares, he has small garters of plain tape, while she has pink silk ribbons. [Figure 1]

|

| Image 1: Garter & stocking of the Lady Clapham doll, V&A Museum |

Further up the social scale garters could be of silk. For the middling sort this might make them important enough to be mentioned in wills. In 1626 George Piner, a tailor, leaves a friend his “best cloak, best suit, [and] silk garters” (7 p. 48), and in 1620 a yeoman, Hugh Butcher [of interest to none but me, my eight greats uncle] leaves, “to kinsman John Writhock” his best silk garters. (8 p. 46)

In the first half of the century, at the top of the social scale amongst the nobility and royalty, garters could be highly embellished with embroidery and lace. The 1617 wardrobe inventory of Richard, 3rd Earl of Dorset, shows that his garters were made to match his suits, for example a suit with a doublet of green cloth of gold, and breeches of green velvet, has “one paire of greene taffetie garters embroadered all over and edged about with a small edging lace of gold”, to match them. (9 p. 48) [Figure 2] The garters could also be made with matching shoe roses and points to hold the doublet to the breeches, one example in King Charles I’s wardrobe accounts is “one paire of rich needleworke garters cinnamond cullor with roses and points suitable to them”. These were not the richest of Charles’s garters, though even the King might have things repaired or remade, “for new makeing twoe rich diamond garters with gould cheines and studs upon watched velvet”. (10 pp. 85, 84)

|

| Image 2: Detail from Larkin's portrait of Edward Sackville. English Heritage |

Narrower garters could be woven with phrases in them. One specific type is the so called “Jerusalem” garter, these were made in the middle east of tablet woven silks for visiting westerners. An example in the Colonial Williamsburg collection is woven with the date 1649. [Figure 3] The Victoria andAlbert Museum, has three examples two of which are dated. One in green, pink and cream silk has in silver, “Edward Guile, Jerusalem, 1677” Another says “Mary Horwood, Jerusalem, 1678”. There is a written reference to Jerusalem garters in the diary of Judge Samuel Sewell(1652-1730) of Boston, Massachusetts, in 1688 he writes about a pair of garters given to him as thanks for money sent to aid colonial American prisoners held by pirates in Algerian jails, “Gee presents me with a pair of Jerusalem Garters which cost above 2 pieces 8 (Spanish mille dollars) in Algier; were made by a Jew”.

|

| Image 3: 1649 garter in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection |

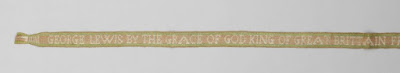

Garters with mottos could have political comments on them. One survival dated 1714 states “George Lewis by the Grace of God King of Great Britain France and Ireland”. [Figure 4] They could also have more personal mottos: a pair in the Manchester Museum collection, dated 1717, has one garter stating “My ♥ is fixt I cannot range” and the other “I like my choice to well to change”, They may have been bridal garters, by the end of the seventeenth century Henri Misson was describing how, after a wedding, “the bride men pull off the bride’s garters “which she will have already undone, and they then wear them in their hats”. (11 p. 64)

|

| Image 4: Garter for the accession of George I. Victoria and Albert Museum |

Leather garters were certainly around, in 1671 James Master paid 6s for “a pa of leathern garters”. (12 p. 142)

Size and fastening

The fashionable garters at the beginning of the century could be very large, one 1611 will gives, “To my mother and sister a pair of skye coloured garters to make each of them a girdle”, implying that each was long enough to fit around a waist. (13 p. 63) In the Oxinden letters two men, who in 1667 were accompanying a bride to church for her wedding, were to have “white garters a quarter of a yard deep with siller lace at ends”. (11 p. 65)

Narrow garters made of ribbon or tape were much narrower, and were worn by the common sort through out the century, and by the elite once the fashion for large garters had passed. The surviving Jerusalem garters may be indicative of size, they are between 110 and 175 cm long (43 to 68 inches) and around 2 to 2.5cm wide (three quarters of an inch to an inch) The Jerusalem garters have a loop at one end and the threads at the other end are braided, and then form a tassel. Other surviving garters do not have this, the ends are either fringed or hemmed.

By the end of the seventeenth century, it was common for men to “roll” their stockings. This meant that the garter became invisible as the stocking was rolled over the garter.

Colours

The colour of garters is not often mentioned in wills and inventories. In 1621 Henry Fletcher, a merchant tailor left “a per of French grene silke garters”, and in 1667 John Leadbeater, a gentleman, left one son tawny garters, and another son his black silk garters. (14 p. 103 &190) The Earl of Dorset’s 1617 wardrobe list has garters in lemon, watchet, tawny, purple, sea green, green, crimson, and black, four have gold lace trim and two gold and silver lace. (9) The garters provided to King Charles I also come in a wide range of colours including; pinck, deer, cinnamon, watchet, black, and white. (10) The account book of Rachel, Countess of Bath in 1650 has “3 yards of blue gartering for my Lady 5s.” (4 p. 154)

Price

Like most clothing, garters were used by everyone from the very poor to the very rich. For the common sort garters purchased ready-made varied in price. In 1634 Thomas Nelmes, a Bristol grocer, had 42 pairs in stock, the cheapest could be purchased for 2d a pair, while his Manchester garters were over 6d a pair. (15 p. 84) In 1642 the Newcastle chapman William Mackerrell had garters from between 2½d and 5d. (16 pp. 186-90) In 1679 the Lincoln haberdasher Henry Mitchell’s garters were considerably more expensive at 1s 3d a pair, with gold garters at 5s a pair. (17 p. 60) The nobility pay more for their silk garters. In the 1640s the Earl and Countess of Bath pay between 4s and 6s for garters, with 18s being “paid for my Lord's garters and roses 18s,” indicating that matching shoe roses were bought at the same time. (4) Prince Henry in 1608 purchases specifically “Naples silk garters at 8s the pair” another pair of silk garters that he buys are 12s. (18) Even more expensive were the gold and silver garters in the stock of Stephen Frewen in 1640, they cost £2 a pair. (1) When Nicholas Le Strange married in 1630 he spent on his wedding outfits the vast sum of £161 12s 1d, four pounds of this was spent on a pair of garters, and 22s on shoe roses. (19 p. 131)

Conclusion

Garters were worn by everyone and could run from a cheap piece of fabric, to something covered in gold embroidery with metallic lace and even jewels. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, for men they were a fashion statement to be made to match shoe roses, points and even hatbands and sword hangers. By the end of the century, they had disappeared from sight with the fashion for stockings rolled over the garters. For women they were always invisible, except perhaps when they wanted them to be visible, as Wycherley has one of his characters say in his Dancing Master, “I have taken occasion to garter my stockings before him, as if unawares of him; for a good leg and foot, with good shoes and stockings, are very provoking, as they say.”

References

1. Cooper, William Durant. Extracts from Account-Books of the Everden and Frewen Families in the Seventeenth Century. Sussex Archaeological Collections. 1851, Vol. 4, pp. 24-30.

2. Kent Archaeological Society. Kentish Documents, c.1530-1810 - A Transcription Project. Available from: https://www.kentarchaeology.org.uk/13/01/52.pdf. [Online] 2015. [Cited: 3 June 2022.] https://www.kentarchaeology.org.uk/13/01/52.pdf.

3. Warner, William. Albion's England. London : Widow Orwin, 1597.

4. Gray, Todd. Devon Household Accounts 1627-59. Part 2 . Exeter : Devon and Cornwall Record Society, new series, vol. 39, 1996.

5. Vaisey, D. G. A Charlbury mercer's shop 1623 (viz 1632). Oxoniensia. 1966, Vol. 31, 101-16.

6. Williams, Lorelei and Thomson, Sally. Marlborough Probate Inventories 1591-1775. Chippenham : Wiltshire Record Society, 2007.

7. Brinkworth E.R.C. and Gibson, J.S.W. eds. Banbury wills and inventories. Pt.2, 1621-1650. Banbury Historical Society. 1976, Vol. 14.

8. Allen, M. E. ed. Wills in the Archdeaconry of Suffolk 1620-1624. Woodbridge : Suffolk Records Society, 1988.

9. MacTaggart, Peter and MacTaggart, Ann. The Rich Wearing Apparel of Richard, 3rd Earl of Dorset. Costume. 1980, Vol. 14.

10. Strong, Roy. Charles I's clothes for the years 1633-1635. Costume. 1980, Vol. 14, pp. 73-89.

11. Cunnington, Phillis and Lucas, Catherine. Costume for births, marriages and deaths. London : Black, 1972.

12. Robertson, S. The expense Book of James Master 1646-1676 [Part 4, 1663-1676], transcribed by Mrs Dallison. Archaeologia Cantiana. 1889, pp. 114-168.

13. Cunnington, C. Willett and Cunnington, Phillis. Handbook of English costume in the 17th century. 3rd ed. London : Faber, 1972.

14. Earwaker, J.P. Lancashire and Cheshire wills and inventories 1572-1696. Manchester : Chetham Society, 1893.

15. George, E. and S. eds. Bristol probate inventories, Part 1: 1542-1650. Bristol Records Society publication. 2002, Vol. 54.

16. Spufford, Margaret. The great reclothing of rural England: petty chapman and their wares in the seventeenth century. London : Hambledon Press, 1984.

17. Johnston, J. A. Probate inventories of Lincoln citizens 1661-1714. Woodbridge : Boydell, for the Lincoln Record Society, 1991.

18. Bray, W. Extract from the Wardrobe Account of Prince Henry, eldest son of King James I. Archaeologia. 1794, Vol. 11, pp. 88-96.

19. Whittle, Jane and Griffiths, Elizabeth. Consumption and Gender in the Early Seventeenth Century Household. Oxford : OUP, 2012.